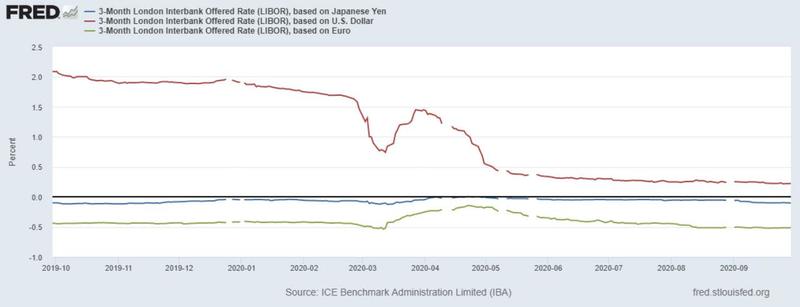

(Christopher Whalen) Watching the talking heads pondering the next move in US interest rates, we are often amazed at the domestic perspective that dominates these discussions. Just as the Federal Open Market Committee never speaks about foreign anything when discussing interest rate policy, so too most observers largely ignore the offshore markets. Yen, dollar and euro LIBOR spreads are shown below.

Zoltan Pozsar, the influential money-market strategist at Credit Suisse (NYSE:CS), warns that the short-end of the US money markets are likely to be awash in cash over the end-of-year liquidity hump. Unlike the unpleasantness in 2018, for example, we may see instead a surfeit of lending as banks scramble for yield in a wasteland bereft of duration. Would that it were so.

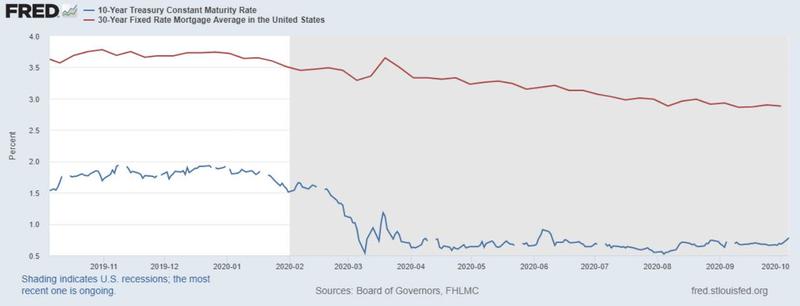

The Pozsar view does not exactly fit well with the rising rate, end of the world scenario popular in some corners of the financial media ghetto. The 10-year note is certainly rising and with it the 30-year mortgage rate. Indeed, Pozsar reminds CS clients that yen/$ swaps are now yielding well-above Treasury yields for seven years. Hmm.

We believe short-term rates will remain low in the US, even as offshore demand for dollars soars. If the 10-year Treasury backs up much further, then we’d look for the FOMC to act on some calls by governors to buy longer duration securities. That is, a very direct and large scale increase in QE and particularly on the long end of the curve.

We expect that Chairman Powell knows that underneath the comfortable blanket of low interest rates lie some truly appalling credit problems ahead for the global economy, the US banking sector and also for private debt and equity investors. We expect the low interest rate environment to drive volumes in corporate debt and residential mortgages, even as other sectors like ABS languish and commercial real estate gets well and truly crushed.

“The pandemic is putting unprecedented stress on CMBS markets that even the Fed is having difficulty offsetting,” writes Ralph Delguidice at Pavilion Global Markets.

“Limited reserves are being exhausted even as rent collection and occupancy levels remain serious issues… Bondholders expecting cash are getting keys instead, and in our view, ratings downgrades and significant losses are now only a formality.”

We noted several months ago that the resolution of the credit collapse in commercial mortgage backed securities or CMBS will be very different from when a bank owns the mortgage. As we discussed with one banker this week over breakfast in Midtown Manhattan, holding the mortgage and even some equity in a prime property allows for time to recover value.

With CMBS, the “AAA” tranche is first in line, thus the seniors have no incentive to make nice with the subordinate investors. The deals will liquidate, the property will be sold and the junior bond investors will take 100% losses. But as Delguidice and others note with increasing frequency, this time around the “AAA” investors are getting hit too. More to come.

Manhattan

Meanwhile, over in the relative calm of the agency collateral markets, large, yield hungry money center banks led by Wells Fargo & Co are deploying liquidity to buy billions of dollars in delinquent government loans out of MBS pools.

The bank buys the asset and gives the investor par, with a smidgen of interest. Market now has more cash, but less cash than it had before buying the mortgage bond in the first place. Why? Because it likely took a loss on the transaction. Buy at 109. Prepayment at par six months later. You get the idea.

In fact, if you look at the Treasury yield curve, rates are basically lying flat along the bottom of the chart out to 48 months. Why? Because this nice fellow named Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, along with many other buyers, are gobbling up the available supply of risk free assets inside of five years.

Spreads on everything from junk bonds to agency mortgage passthroughs are contracting, suggesting that the private bid for paper remains strong. When you look at the fact that implied valuations for new production MBS and mortgage servicing rights (MSR) have been rising since July, this even though prepayment rates are astronomical, certainly implies that there is a great deal of cash sitting on the sidelines.

Remember that the price of an MSR is not just about cash flows and prepayments, but it’s also about default rates and the relationship with the consumer. We described in our last missive for The IRA Premium Service (“The Bear Case for Mortgage Lenders”), that a rising rate environment could generate catastrophic losses for residential lenders, particularly in the government loan market. We write:

“For both investors and risk professionals operating in the secondary mortgage market, the next several years contain both great opportunities and considerable risks. We look for the top lenders and servicers to survive the coming winter of default resolution that must inevitably follow a period of low interest rates by the FOMC. The result of the inevitable consolidation will be fewer, larger IMBs.”

Don’t get distracted by the rising rate song from the Street. We don’t look for short or medium term interest rates to rise in the near term or frankly for years. Agency 1.5% coupons “did not find a place in the latest Fed’s purchase schedule. It is possible (they) are included in the next update,” writes Nomura this week. This seems a pretty direct prediction of lower yields. But as one veteran mortgage operator cautions The IRA: “Not just yet.”

We don’t think that the Fed is going to take its foot off the short end of the curve anytime soon, in part because the system simply cannot withstand a sustained period of rising rates. In fact, we note that our friends at SitusAMC are adding 1.5% MBS coupons to forward rate models this month. But that does not necessarily mean that mortgage rates will fall any time soon.

We hear that the Fed of New York has bought a few 1.5s in recent days, but supply is sorely lacking. You see, the mortgage industry is not quite ready to print many new 1.5% MBS coupons and will not do so anytime soon. As the chart above suggests, mortgage rates are in fact rising. Why? Is not the FOMC in charge of the U.S mortgage market?

No, the market rules. Today you can make more money selling a new 1-4 family residential mortgage into a 2.5% coupon from Fannie, Freddie or Ginnie Mae at 105. You book a five point gain on sale and are therefore a hero. And a year from now, after the liquidity does in fact migrate down to 1.5s c/o the beneficence of the FOMC, you can again be a hero.

Specifically, you call up that same borrower and refinance the mortgage into a brand new 1.5% Fannie, Freddie or Ginnie Mae at 105. You take another five point gain on sale. Right? And who paid for this blessed optionality? The Bank of Japan, Peoples Bank of China, and PIMCO, among many other fortunate global investors.

These multinational holders of US mortgage bonds may not like negative returns on risk free American assets, but that’s life in the big city. And thankfully for Chairman Powell, it’s not his problem. Many years ago, a friend in the mortgage market said of loan repurchase demands from Fannie Mae: “What do you want from me?”