Summary

- Saudis want Big Oil to win – have predictable working relationship with them.

- Big Oil is waiting on the sidelines until the price of properties drop.

- Those with DUC wells and enough reserves will be able to survive the onslaught.

- U.S. shale oil remains viable, but the players are going to change.

As the strategy of Saudi Arabia becomes clearer, along with the response of shale producers to low oil prices, the question now has to be asked as to whether or not the big oil companies support the decision by Saudi Arabia to crush frackers until they have to offer their various plays at fire sale prices.

With the emergence of frackers came a significant number of new competitors in the market that didn’t have an interest in playing nice with OPEC and Saudi Arabia, as major oil companies have in the past. This was a real threat as other OPEC members and shale companies started to take share away from Saudi Arabia.

The general consensus is Saudi Arabia isn’t interested in crushing any particular competitor, rather it’ll keep production at high levels until the weakest producers capitulate. I have thought that as well until recently.

What changed my thinking was analyzing who was the biggest threat to OPEC and Saudi Arabia, and in fact it is the shale industry in the U.S. The reason I draw that conclusion is the energy industry had its traditional competitors in place for many years, and other than occasional moves to impact the price of oil using production levels as the weapon, it has been a relatively stable industry. Shale changed all that.

I think what bothered Saudi Arabia in particular was it didn’t have a working relationship with many of these new competitors, who have been very aggressive with expanding production capacity over the last few years. They were in fact real competitors who were working to take market share away from existing players. And with Saudi Arabia being the low-cost producer with the highest reserves in the world, it was without a doubt a direct assault on its authority and leverage it historically has had on the oil market. Its response to frackers is obvious: it isn’t willing to give up share for any reason.

Where the challenge for Saudi Arabia now is it has started to have to draw on its own reserves and issue bonds to make up for budget shortfalls. It has plenty of reserves, but it appears we now have a clear picture on when it would really come under pressure, which is within a four to five year period. That’s the time it has to devastate its shale competitors.

The other problem for the country is it could take down some members of OPEC in the process, where there are already significant problems they’re facing, which could lead to unrest.

From a pure oil perspective, it seems to be an easy read. Saudi Arabia can outlast the small shale producers with no problem. I think that’s its goal. But it is putting enormous pressure on other countries as well, and there will be increasing pressure for them to slow production in order to support oil prices.

This even extends to Russia, which produces more oil than any other country.

My belief is Saudi Arabia is attempting to force consolidation in the shale industry, so it can resume its dealings with big oil players it has worked with for many years. I believe it’s also what big oil players want. All they have to do is sit back and experience some temporary pain and wait for some of the attractive plays to come onto the market at low prices.

So far the price is still high in the U.S., but as time goes on, the smaller companies will be forced to sell, one way or another. That’s the big opportunity for investors. Identifying those companies with the resources and desire to acquire these properties is the key. That and evaluating the plays with the most potential for those buying them up.

At what price can Saudi crush shale oil?

There are analysts predicting oil price levels that are all over the board. I’ve seen those that believe it’s going to shoot up to over $100 per barrel again, and those that have estimated it could fall to as low as $15 per barrel.

The best way to analyze this is to consider what Saudi Arabia can handle over the longest period of time without destroying its own economy and industry, meaning at what price it can remain fairly healthy and outlast its competitors.

Looking at the price movement of oil and the range it’s now settled into, I think it’s close to what the Saudi have been looking for.

Most smaller shale producers will struggle to make it, if the price of oil remains under $60 per barrel, which it will probably do until Saudi Arabia cuts back on production. There will be occasional moves above that, and probably below $50 per barrel again as well, but I think we can now look to somewhere in the $50 per barrel area as the target being sought. We’ll probably see this be the price range oil will move in for the next couple of years, with $50 being the desired low and $60 being the desired high.

I don’t mean by this Saudi Arabia can absolutely control the price of oil, but it can influence the range it operates in, and I think that’s where we are now.

For that reason oil investors should be safe in investing under these assumptions, understanding there will be occasional price moves outside of that range because of usual trading momentum.

Response from shale oil companies

Some may question why the price of oil got slammed not too long ago, falling below $40 per barrel, if the probable price range for oil is about $10 to $20 per barrel higher.

As mentioned above, some of that was simply from trading momentum. It didn’t take long for it to rebound soon afterward.

The other element was the response by shale companies to the new price of oil, which threatened their ability to pay interest on loans that were due.

Frackers weren’t boosting production because they believed they could outlast Saudi Arabia; they kept production levels high because they had to continue to sell even into that low-price environment or default on their payments. This was a major factor in why prices dropped so far over the short term.

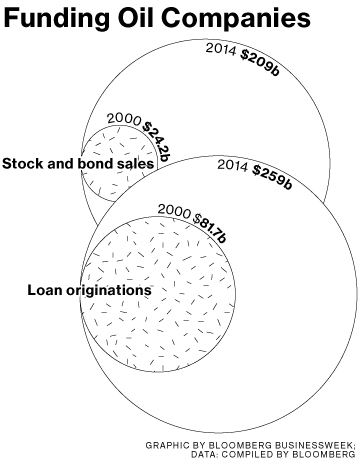

With the bulk of the over $5 trillion spent on shale exploration and development coming from companies operating in the U.S., that is also where the bulk of the risk is.

Much of the efficiencies have been wrung out of operations, and moving to higher producing wells that are less costly to operate can only last so long. I believe efficiencies will position some in the industry to survive the current competitive environment, but they will also have to have enough reserves to tap into in order to do so.

Top producing shale wells are at their highest level of productivity in the first 6 months it goes into operation. It gradually fades after that.

Larger players like EOG Resources (NYSE:EOG) have continued to drill, but they are stopping short of production, with approximately 320 DUC wells ready to bring online when the price of oil reaches desired levels. Its smaller competitors don’t have the resources to wait out existing production levels, which is what will again offer the opportunity for patient investors.

In other words, most of what can be done has been or is currently being done, and from now on it’s simply a waiting game to see how long the Saudis are willing to keep the oil flowing.

Most shale producers believed the lowest oil prices would sustainably fall and would be about $70 per barrel. Decisions were made based upon that assumption.

Big oil and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia and big international energy companies have had close relationships a long time via Saudi Aramco, the state-owned firm.

Those relationships, while competitive, still operated within parameters most agreed upon. Shale producers weren’t playing that game, as they invested trillions and aggressively went after market share. If Saudi Arabia wanted to maintain market share, it had to respond.

If the smaller shale producers thought their strategy though, they must have underestimated the will of Saudi Arabia to fight back against them. Either that or they became overly optimistic and started to believe their own press about the shale revolution.

It’s a revolution for sure, but the majority of those that helped launch it won’t be finishing it.

My point is big oil, in my opinion, doesn’t mind quietly standing on the sidelines as their somewhat friendly competitors destroys their competition and prepares the way for them to acquire shale properties at extremely attractive prices.

I’ve said for some time the shale revolution will go on. The oil isn’t going anywhere. What is changing is who the players will end up being, and what properties they’ll end up acquiring.

With EOG, the strongest shale player, it said the prices of those plays now for sale are still too high; that means the smaller players still think they have some leverage.

My only thought is they are hoping for the large players to enter a bidding war and they can at least recoup some of their capital. I think they’re going to wait until they’re desperate and have no more options.

Sure, some big players may lose out on a desirable property or two, but everyone will get a piece of the action. It appears once the prices move down to levels they’re looking for, at that time they’ll swoop in and make their bids. At that time it’s going to be a buyer’s market.

Big oil companies are the preferable players Saudi Arabia wants to do business with and compete against. They will play the game with them, and there won’t be a lot of surprises.

Some of the companies to watch

Some of the larger companies that have already filed for bankruptcy this year include Hercules Offshore (NASDAQ:HERO), Sabine Oil & Gas (SOGC) and Quicksilver Resources (OTCPK:KWKAQ).

Companies known to have hired advisers for that purpose are Swift Energy (NYSE:SFY) and Energy XXI Ltd. (NASDAQ:EXXI).

Some under heavy pressure include Halcón Resources Corporation (NYSE:HK), SandRidge Energy, Inc. (NYSE:SD) and Rex Energy Corporation (NASDAQ:REXX).

There are more in each category, but I included only those that had at least a decent market cap, with the exception of those that already declared bankruptcy.

Here are a couple of other companies to look at going forward, which can be used for the purpose of analyzing ongoing low prices.

Stone Energy’s credit facility of $500 million is reaffirmed, but may not be liquid enough to endure the next couple of years, even though in the short term it does have decent liquidity. If Saudi Arabia keeps up the pressure, it’s doubtful it will be able to survive on its own. There are quite a few companies falling under these parameters, including Laredo (NYSE:LPI). The basic practice of all of them was to limit the amount of leverage they have in place in order not to have paying off interest as the priority use of their capital, while maintaining a strong credit facility.

I’m not saying these companies will survive, but they will survive if the price of oil stays low, but it will take a lot more to root them up than their highly leveraged peers.

Clayton Williams (NYSE:CWEI) recently put itself up for sale because it can’t afford to continue operating at these prices. It has approximately 340,000 acres under its control, and two of the most productive shale basins in the U.S.

Once it announced it was open to selling, the share price skyrocketed, but since it’s struggling to afford extracting the oil, it’s puzzling as to why some believe it’s going to attract a premium price. It’s possible because of the quality of assets, but it would make more sense for larger companies to wait.

This will be a good test on how big oil companies are going to respond. It’s possible they may be willing to pay for the higher quality shale plays, but under these conditions shareholders would resist paying a significant premium.

If Clayton Williams does go for a premium, it doesn’t in any way mean that’s how it’ll work out for most of the shale companies.

There would have to be a significant reason they would pay such a high price. In the case of CWEI, the catalyst would be high production.

Conclusion

All of this sounds neatly packaged, and if all things proceed as planned, this is how it will play out.

Where there could be some risk is if the Middle East explodes and oil production is interrupted. That would change this entire scenario, and if it were to happen soon, shale companies still in operation would not only survive, but thrive.

Barring that level of disruption, which would have to be something huge, this is how it will play out. After all, with everything going on there now, it hasn’t done anything to disrupt Middle East oil. It would take a big event or a series of events to bring it about. That’s definitely a possibility, but it’s one that is unlikely.

Once all of this plays out, there is no doubt in my mind the bigger oil companies will be much stronger and able to produce a lot more oil.

What we’ll probably see happen is for them to cut back on production to levels where everyone is happy, including the Saudi.

That’s what this war is all about, because shale oil deposits remain in the ground. While some companies can quickly resume production because of the nature of shale oil, which can ramp up production fast, it depends on the will and determination of Saudi Arabia and whether or not the geopolitical situation remains under control.

I don’t care too much about the number of rig counts in shale plays because production can be resumed or initiated quick. The risk is how leveraged the shale companies are, and whether or not they have to continue production at a loss in order to pay off their interest on loans in hopes the price of oil will rise.

What I’m looking for with existing plays is for companies like EOG Resources, which continues to develop wells, but does so without the idea of completing them and bringing them into production until the price of oil rebounds.

Shale oil in the U.S. is alive and well, but those companies overextended and few resources are going to be forced to sell at bargain prices. That will produce a lot of added value to the big oil companies waiting on the sidelines watching it all unfold.

Read more by Gary Bourgeault on Seeking Alpha

Oilfield worker on a rig

Oilfield worker on a rig

You must be logged in to post a comment.